Sámegillii

Sámegillii  På norsk

På norsk

Article in the book Sami School History 2. Davvi Girji 2007.

Svein Lund 2005. |

Svein Lund is the main editor of «Sami school history». He was born in 1951, grew up in Skien and has lived in North Norway since 1973. He attended Trondarnes folk high school and studied mechanics in Guovdageaidnu and Hammerfest. After working as a mechanic in the fish-processing industry in Hammerfest for almost a decade he attended the technical school and was teaching mechanical subjects in upper secondary school in Guovdageaidnu 1988–98. He has additional education in pedagogy, Norwegian and Sami. More recently he has worked on education research and as a supply teacher as well as with writing books and articles. He has published, among other books, Samisk skole eller Norsk Standard? (Sami school or Norwegian Standard?) |

We are hundreds, maybe thousands, of southerners who have been involved in schools for Sami throughout the times. I have experienced various forms of Sami education myself, both as pupil, student, teacher, representative and writer. Following are a few glimpses of my experiences.

|

|

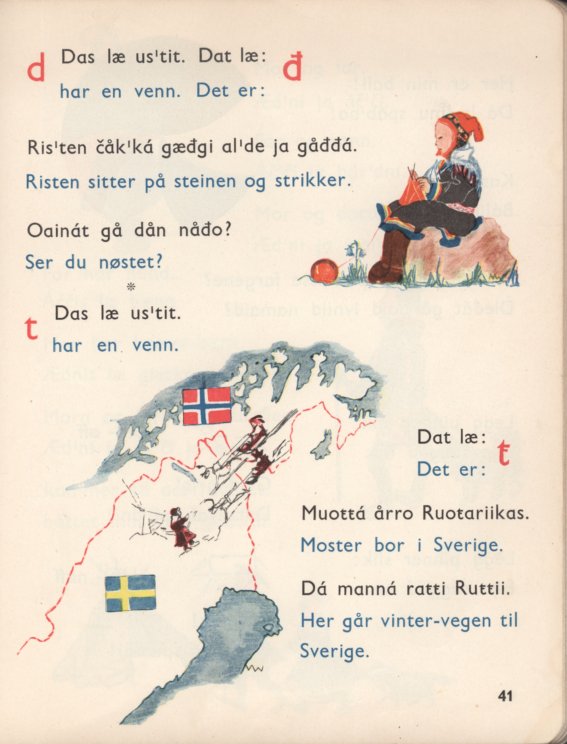

From Margarethe Wiig's Sami-Norwegian ABC. |

I did not learn a lot about Sami in school, but apparently enough to make this drawing. |

I must have been about 8–9-years old when my father came back from school with Margarethe Wiig's Sami–Norwegian ABC. I still remember how fascinated I was of the colourful drawings of the life on the plain in Finnmark, and not least by the language with strange letters such as č, š and ŧ. This book must have instilled a longing in me to get to know this people and this language.

This was the first time I experienced that Sami knowledge wasn't something to be proud of, but something you kept a low profile with. Up to this day I have no idea how many of my classmates who had Sami background. It was probably far more than the one I understood was Sami, but who never told it openly.

My first year in the north gave me a taste for more, and I needed a vocational training. I discovered a vocational- and handicraft school in Kautokeino in the brochure of vocational schools in Finnmark. In addition it was a Sami school, it was written, and thus I could kill two birds with one stone. To my surprise I was admitted. Finally I was to learn the language I had barely seen since the ABC-book in my childhood. I got hold of a small Sami glossary for using at school. With Sámegiel skuv'lasádnelis'to in my backpack I hitch-hiked in Northern-Norway trying to prepare for what I was to meet.

In Guovdageaidnu I found a different attitude to Sami than what I had experienced in Harstad. But although the people here were Sami and wanted to be so, the school I met here in 1974 on the whole was a traditional Norwegian vocational school. Our class teacher neither spoke nor understood Sami. He came from the coast of Finnmark, but I didn't discover that he had a Sami background until years later. About half of the pupils at the school were Sami speaking, but only a couple of the teachers. None of the teachers could write Sami, which meant that a teacher from primary school had to be recruited for the very limited Sami education offered. Sami was only a mandatory subject at the course of study of sewing and weaving, with one lesson a week. We who attended other courses of study got the possibility to participate. At the elementary course we were only two who did so. It was possible to get the diploma from the Sami vocational-and handicraft school without knowing a single word of Sami, as both teaching and textbooks were in Norwegian.

|

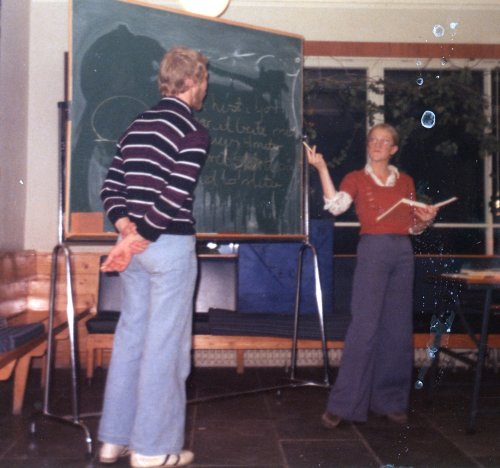

On Saturday evenings we often arranged pupil's-evenings, and many of the girls would dress up in national costumes. |

The least Sami course of study was probably the one I attended, machine- and mechanic. We had a centrally decided set of exercises, none of them were connected to Sami or local culture and tradition. At the end of the year we could make some independent projects, but I can't remember that we made anything typical Sami.The workshop was also so small that it was impossible to take in bigger machines for repairing. The space between the machines was incredibly narrow. Not untl 30 years later did I read what the principal thought about the matter in the annual report of the school for 1974/75: «The schoolroom of the machine- and mechanics department is not satisfactory». Yet 7 years would pass until it was improved.

In the carpenter course of study they mainly made normal furniture, but it also happened that pupils made wooden cups (guksi) and such to themselves in Sami style.

The course of study with most Sami content was without a doubt «sewing and weaving». The pupils sewed Sami hats, national costumes and fur shoes, and wove shawls for the national costumes and bands for fur shoes. Their teacher committed herself to giving her pupils a Sami education. She wore the national costume herself, spoke Sami when teaching, and it is probably in great part her achivement that Sami handicrafts was made part of the education again after being replaced to a large extent by ordinary Norwegian «sewing of dress- and suit» in the 1960s.

The last course of study was domestic science. They had a Sami speaking teacher, but I don't know much about what they were doing, as their practical teaching took place in the upper primary school because there was no kitchen in the vocational school.

The year I studied at the school the pupils were very active. Among other things we arranged pupil's evenings on Saturday, where also some of the teachers took part. In one of these evenings we made a skit where it was said that the only Sami thing about the school was the name – which was in Norwegian. Both Sami and Norwegian pupils found it strange that there was so little Sami content and language in the school.

The pupils were registered collectively in the Special interest organisation of pupils in vocational schools and apprentices (YLI), and we had our own YLI-group in school. Among other things we made a claim to get Sami textbooks through the regional committee in Finnmark and at the national meeting of YLI in 1975.

|

The student council performing a skit on a pupil's evening, 1974/75. When all common activities in school took place in Norwegian, it was probably not a coincidence that the Norwegian speaking pupils were dominating these. Among the five representatives in the student council none had Sami as their mother tongue. Left: Per Aarseth, machine- and mechanics, Bente Dolmen Wigelius, sewing and weaving. Right: Bernt Morten Bongo, carpenter 1, Aase Andersgård, carpenter 2, Reidun Eriksen, domestic science. (Photo: Svein Lund) |  |

While I was a pupil there was a change of principal. A monolingual Norwegian speaking principal was succeeded by a Sami speaking principal, and this may have contributed to bring the school more in a Sami direction. At the time the work of the so-called Einejord-committee was in course, which resulted in publishing the report Upper secondary education for Sami in 1975. As far as I remember there were no discussions about this report in school, not until years later did I discover that one of my fellow pupils took part in this committee.

|

The student organization YLI had a campaign day in connection to the state budget for 1975 and YLI-group arranged a get-together for the pupils. Some of the pupils performed a skit about the school, among other things ridiculing a Sami school having all the teaching and information in Norwegian.

From the left: Ann Brit Rauland, Bernt Morten Bongo, Odd Reidar Biti, Lars ?, Nils Harald Boine, Svein Lund.

(Photo: Jon Arild Andersen) |

During the Alta-struggle a change started to take place, and also in Hammerfest Sami started to come forward. Some of them founded a Sami-organisation, which arranged courses in Sami language. Like this I got to revive what I had forgotten, and at the same time learn the new orthography. I threw myself into the Davvin-books when they were published, but somewhere in the third book the interest was lost.

In 1988 I found a notice in the newspaper stating that the Sami secondary school needed a teacher for the mechanical course of study. I threw in an application, and was at least as surprised as last time when the school wanted me. Soon I could enter the school gate I exited 13 years earlier, this time to be a teacher.

Because of the school- and Sami political development in the period 1975–88, I had illusions that this time I would come to a real Sami school. But it turned out I had been far too optimistic. Admittedly the school had courses of study for reindeer husbandry and duodji, but other than that there was not much dividing the school content wise from a normal Norwegian secondary school. Sami language was a subject in most of the courses of study, but there was no lessons in Sami language at the mechanical course of study. The teaching still mainly took place in Norwegian, and with my poor Sami skills I was in good company. About half of the teachers were not able to speak Sami, and very few knew how to write the language.

|  |

| From first year of machine and mechanics 1988/89: Pupil Lars Johan Sara and teacher Isak I. Hætta. (Photo: Svein Lund) |

From second year of farming mechanics 1989-90. From left: Ivar Utsi (duodji-teacher visiting), pupils: Nils Morten Hætta, Intisar Aziz Shaikh and Arnt Isak Oskal. (Photo: Svein Lund) |

Formally, with the exception of pedagogy, I held all the qualifications required to teach at the mechanical course of study. I was to read pedagogy later, a common arrangement in Finnmark at the time.

I must have been a strange figure to the pupils. That I did not know much Sami when I arrived, was probably not that strange, they had been taught by many norwegianizing teachers before. Worse was the fact that I was supposed to be a teacher of mechanics, and had no clue about the main interest of the pupils; to fix vehicles and small machines, such as snow scooter, moped, four-wheeler and chain saw. Certainly I could make use of my knowledge about lathe and milling machines, as this was part of the curriculum, but it was considered much less important than knowledge about snow scooter, moped and car. And the knowledge I had acquired being industrial machinery mechanic in the fish-processing industry was completely irrelevant. I was a fish on shore.

It would be a plain lie to assert that the beginning of my career as a teacher was a great success. But if I would only learn a little pedagogy and some more of the Sami language, everything would improve. It turned out it was not that easy, but I would spend years to figure that out.

When I started teaching I knew quite a lot of Sami words. I read Sami newspapers using the dictionary frequently, but I did not speak, and I quickly got lost when pupils and others spoke with each other in Sami. I did not have a lot of time for studying Sami in addition to my work either, but I was able to attend one evening course, and did the exam for Sami as C-language for upper secondary school. I wrote a small epistle on what happened next in 1990. Here's a small extract of it: It's so wisely organised that if one wishes to learn the Sami language, it's not possible to do so in a Sami-speaking area. Next stop: the northernmost university in the world. At first we spend two-three months learning accusative case and the potential mood by heart, and reading about the Sami culture in olden days in Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish or English, while speaking Norwegian with each other and the teachers, and everything is smooth.

Then it happens. The day it gets serious and all the teaching takes place in this language we desperately have been trying to learn. It's the mother tongue of the new students who enter the class, and they quickly engage in discussions with the teacher. And there we are. Infinitely stupid and unable to understand. (That someone tell us we are clever run off like water on a duck's back. We know better ourselves how stupid we are.) We are able to copy what is written on the blackboard. And then we can look up what it means in the dictionary when we get home. I become the «nicest boy in class». I try to give a smile when the others are roaring with laughter about something which apparently was funny, but I just understood the half of. I go to the cafeteria with the others, but remain in silence also there, as long as no one arrives and makes the language of the conversation change to Norwegian. What happened to the one who always was in opposition and always spoke up? [4]

While studying some of us went to the student newspaper to tell that this organisation was not reasonable. The basic university course was structured for students having Sami as their mother tongue, and there were no separate actions made for those of us who studied the language as a foreign language. Neither the university nor the teachers took any responsibility for us learning practical Sami. We had to try to manage that on our own, in between lectures and the reading list.

The content of the Sami course of study was probably interesting to those who had deep literary, gramatical and historical interests, and maybe useful to those who would teach in the general studies in secondary school. But there was no trace of subject didactics, and no help to get with the lack of terminology for mechanical subjects.

We were eight with different mother tongues than Sami who started the basic course of study. Half of us followed until the exam. Two had Finnish as their mother tongue, they passed. The two of us with Norwegian as mother tongue, failed. The decision of the external examiner was undoubtedly correct, at least in my case.

While studying Sami language, I had to start the pedagogy education. The pedagogy-course turned out to be totally free of topics concerning culture and language, and I still felt very far from being able to teach my subjects in Sami language. But it had to be possible to find help somewhere? When the Sámi University College announced a course on multicultural pedagogy, I was quick to enrol. I learned a lot there, about social anthropology, Africa and New Guinea, immigrants in Oslo and tips for kindergarden and primary school. Undoubtedly useful as a general education. But then there was my job. Vocational training in Sami secondary school.

The following year the Sámi University College offered bilingual pedagogy. Maybe that was what I needed? But no. A lot of ideas on how to carry out bilingual teaching for motivated pupils interested in languages. I kept asking for vocational training for two years – no response.

Later I enrolled for main subject in vocational pedagogy. At last I would be able to merge vocational training with bilingual and multicultural conditions. But the cultural and linguistic dimension turned out to be absent at Akershus University College. On the other hand the discussions on vocational pedagogy made me realize the big error I had made in believing that learning Sami language would solve my pedagogy problems. It would probably have been better if I had bought an old scooter and learned how to repair it, in other words met my pupils where they were at. With or without language. But back to the school in the late 80s.

Contemporaneously another goal of the administration was to make the school more Sami. Both of these goals would meet resistance. We were few who worked to strengthen both the Sami language and content in the vocational training. When the administration, rightly or wrongly, was understood as opponent of the vocational courses, this did not strengthen the work for Sami language and culture within the vocational training. In particular this came to a head when the administration wanted to take half of the floorspace of the workshop of the mechanical course and change it into a room for theoretical teaching.

I experienced to be in the midst of both of these discussions as I was the representative of the teachers in the Vocational Teacher's Union and later in the Teacher's Union. In many ways I have had one foot in each camp. I was the most accademic of the vocational teachers and at times I had more theoretical than practical teaching. At the same time I was one of very few dážat (non-Sami) in the environment who with time both spoke and wrote Sami. These combinations would bring me into more conflicts than I have space to tell about in this article.

The school got a good bit of money for development work. A test leader was employed and a test committee was established, where all departments of the school were represented. A very inspiring environment developed. I would especially like to highlight the test leader and the deputy head 1, which had clear visions for the school and were good at getting development actions started.

The aim of the development work was to improve the pupil's learning environment and well-being in the school. One of the actions was to keep the school open in the evenings, another a social teacher, an offer which sadly only lasted for a year. Furthermore offers for 3-year courses of study were developed, while it had earlier just been courses of study for 1or 2 years.

The school did not have the best starting point for doing a school development. Most of the teachers were lacking a basic training in pedagogy(!), barely anyone had any further education in pedagogy. Quite a few did not have a completed vocational training neither. Except for the Sami teachers few knew how to write Sami. But under these circumstances an improvement of education was started which contributed to both raising the formal teacher qualifications, the level of knowledge and the consciousness about linguistic and pedagogical questions connected to Sami teaching.

There were often courses for teachers in different subjects, from evaluating the school to locally based teaching, bilingualism and Sami history. There were competence-giving courses in vocational pedagogical development work (1989–91) and for guidance pedagogics (1992–93). Sami courses for teachers were started, both for Norwegian speaking at different levels and writing courses for teachers who spoke, but did not write Sami. The use of the Sami language increased, primarily in the administration.

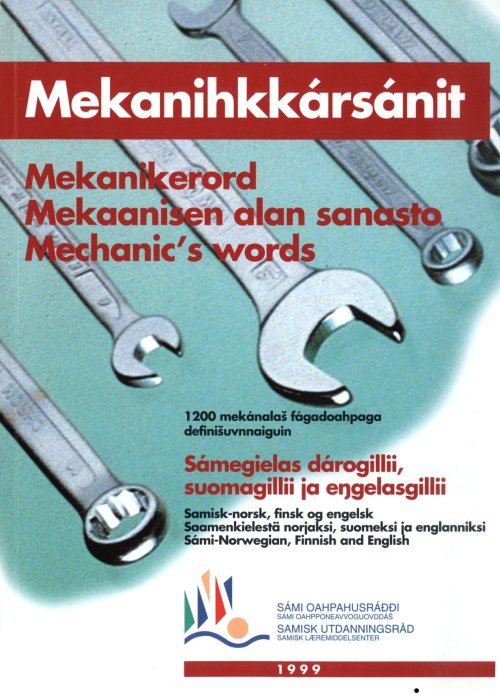

One of the goals for the development work was to develop teaching material. We did not get far with this during the test period, but the work was started, and some of it has been completed later. The work with finding a terminology for mechanical subjects was started. In addition teaching plans and cooperation forms were made, and although they did not result in printed teaching material the pupils benefited from them.

The most important long term effect was probably that the test period changed something in the thinking and attitudes of the teachers. We understood that we could organize the school differently, we could make teaching plans ourselves and even text books. We developed a more critical and simultaneously a more constructive attitude.

As part of my practical-pedagogical education I wrote a project work on the conditions to use Sami as the language of teaching in mechanical subjects. I concluded that before one can write or translate text books, one has to develop a technical terminology. Someone should do something about it, I wrote. Someone who had a wide knowledge of mechanical subjects, had Sami as his mother tongue and knew both grammar and word formation well. But since we did not find anyone with all these qualifications, we had to combine people who had some of the qualifications each. And this is how it came about that a grammar for mechanical subjects was made although no one really had the qualifications to write it. I made the list in Norwegian, and found the English, Swedish and Finnish translations in dictionaries. With the help from another mechanics I wrote the definitions in Norwegian. With a Sami teacher I tried to suggest what this could be called in Sami. The suggestions were sent to a reference group of Sami mechanics and linguists. But none of us were experienced in working with terminology. So we applied for a grant for nordic cooperation and travelled to Iceland to study how they constructed technical terms there. 8 years after I finished writing my project work the book Mekanihkkársánit was printed, containing 1200 technical terms approved by the Sami language council.

|

Looking back at the development of the school over the decade I was employed at the Sami secondary school and reindeer herding school, I would divide it in two more or less equal periods. The first period was characterized by discussion, enthusiasm and progress in the development of the Sami teaching. The second period was marked more by frustration and resignation. Already the teacher's survey in the school year 1993/94 reveals «Stagnation when it comes to realising the main goals in the strategic plan of the school». [5] The annual report of the school 1994/95 tells that the development work was at a standstill. There were both internal and external reasons for this decline. When the test period had come to an end, the source of finance for the development work was gone, and the conditions were more difficult for those who wanted to do something more. Without a separate test leader the administration neither managed to get new actions started, nor follow up properly the ones already started.

But the great backlash came with the Reform 94. While the attitude from central authorities for some time had been characterized by an understanding of what was distinctive with a Sami school, a completely different attitude was set in force through Reform 94. From now on everything should be made uniform. A new division of courses of study, new divisions of subjects and lessons and new curriculums were milled over the school and lead to having to end many of the actions which had been developed through the test period. Reindeer herding and duodji could no longer be subjects of specialization at the general course of study, the freshly made curriculums for three years of education within reindeer herding and duodji had to be thrown away. The duodji education at the school was reduced from three to one year. The development of Sami secondary education was set several years back in time with one blow. For those who were engaged in the work with the curriculum this was a very frustrating experience, as they were overrun by the ministry continuously.

The school administration and the teachers made some attempts to influence the ministry, but did not achieve much. Subsequently one had to adapt reluctantly to the new situation, close down the Sami offers, and to a great extent go back to just running a Norwegian school. Also the board of the Sami secondary schools protested, but wasted their breath in the ministry.

If the Sami Education Council and the Sami Parliament would have involved themselves more things could have changed. There is a striking contrast between the passivity they showed when it came to Reform 94 and the effort both of the agencies demonstrated 3 years later, when it came to the primary school.

Another reason why the frustration replaced the enthusiasm was the administration's lack of abilities to follow up plans and lack of will to listen to initiatives from the teachers. From 1991 on there were developed strategical plans, with main goals and intermediate aims for each plan period. Many got involved in working with the plans, but when the plan was finished it was just put aside in a drawer. And it would rest there until it was to be changed three years later.

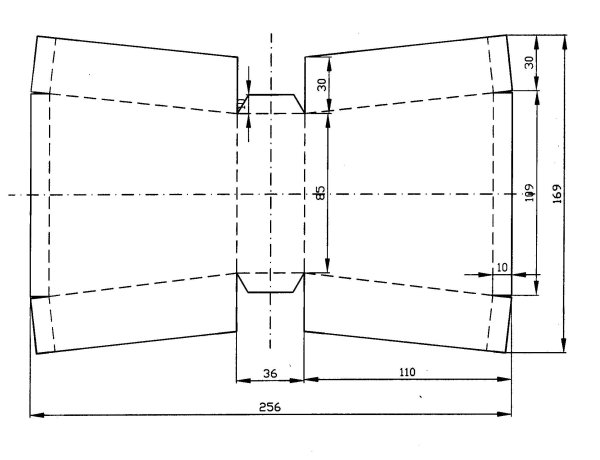

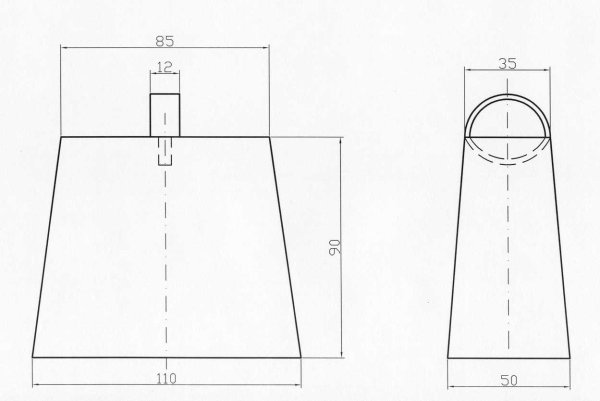

The most important development work I took part in, was run without any resolution from any authority, and no additional grants. I'm thinking about the work with giving a Sami content to the practical education in mechanical subjects. For decades iron and metal / machine and mechanics had a fixed set of exercises. When I returned to the school as a teacher in 1988, we were still to a great extent using this. Contemporaneously the teachers had already started to develop exercises connected to Sami tradition and daily life, and I joined them in developing this. The first exercise was to make a knife, the second a shaft for a snow scooter sleigh. With time we developed a new set of exercises, where we used some things we found in different books and some things we drew ourselves. In addition to knife and shaft with time we developed a bell, a jiehkku (leather scraper) and skjerding. [6] We made working drawings and in part working instructions. In addition to several of the teachers at times some of the pupils took part in this work as well.

|

To make traditional Sami ironwork part of mechanical subjects, we made working drawings with the computer. This one is drawn after an old reindeer bell we got in for reparation. (Drawing: Svein Lund) |  |

Not until 4-5 years after I quit working in the school did I start to summarise this work and try to continue to develop it a bit further. It ended in the manuscript Jernarbeid i samisk tradisjon (Ironwork in Sami tradition), which unfortunately it seems will never be printed, as no one is willing to finance it. [7]

In principle I was of the opinion that in Sami secondary school the language of teaching should be Sami. But the step from conviction to actually putting it in action myself was long. The first thing to do was of course to learn the Sami language. Before going to Tromsø I had been speaking Norwegian with everybody in school, both teachers and pupils. The long and difficult process of changing language started when I moved back to Guovdageaidnu. Most of the people I knew from before continued to speak Norwegian to me out of habit. It was mostly those with language awareness who spoke Sami to me. And I must admit they did not make things easy for themselves. One of them later told me how difficult it was in the beginning. She often had to wait while I was thinking and formulated words and phrases trying to get to what I wanted to say. And she had to speak very slow and repeat to be sure I understood everything. But some had that patience, because they found it important that more people learned Sami and started to use the language. I'm thankful to them. Without the first patient language changers I would have resigned, and Sami would have remained a passive language for me as it is to many others.

The teacher environment at mechanical subjects on the other hand remained an island of the Norwegian language to a large extent. Indeed everybody understood Sami, and most of us could speak the language, but the Sami speaking teachers here did not see the point in speaking Sami with me when we understood each other better in Norwegian. Still the greatest challenge was the pupils. The first condition to teach in Sami was to speak Sami with the pupils also when we spoke informally. Just like the teachers the pupils had different attitudes. Some used the Sami language consistently. Even when I spoke Norwegian in class they would speak to me in Sami. Others could use both languages, while some of the Sami speaking pupils would consistently speak Norwegian to me.

I had spent a lot of time learning the Sami language, and when it came to knowledge about the language, I had come a long way. At the university there was a great emphasis on consistent use of Sami words, and to make use of new Sami terminology. We tried to get rid of the Norwegianisms in the language. The problem was that the youth did not speak the language we had learned in university. A lot simply had to be un-learned. I had to learn when it's common to use Norwegian loan words and adapt my Sami to reality. Among mechanics, mechanics pupils and mechanics teachers in Guovdageaidnu the language was a means of communication, not an aim in itself. They did not see any use in changing words which worked and everybody understood, just because some academic had invented another word which apparently should be more genuinely Sami.

The first challenge was to be accepted as a user of the Sami language. The second was to make the language work well in professional and pedagogical circumstances. Not only did we lack text books, there was also a complete lack of material in Sami on our subject area. No books, no instructions, no articles. When the grammar with the technical terms was ready we used these words to label the shelves with tools. It looked good when we did guided tours of the school, but it did not mean much to the pupils. Most of the time they did not read the labels in any language, but simply took the tool needed based on the shape and put it back where they found it suitable. To learn the language the labels had a minimal effect.

Although I knew a lot of freshly constructed terms, I could not teach the pupils a language which was their mother tongue and a foreign language to me. I was far behind both the pupils and the Sami speaking teachers when it came to oral understanding and speaking, but ahead when it came to reading and writing. I spent a lot of time writing letters, teaching plans and tests to the pupils and teachers in Sami. When they got texts in Sami from the school, they were used to having Sami on one side and Norwegian on the other. When I handed out such papers with the Sami side up, most of the pupils would turn the page to read the Norwegian text. They would only read the Sami text if there was no Norwegian text on the backside. But most of the time it was, because there was almost always some pupils and/or teachers who did not understand the Sami language.

I enjoyed teaching pupils, but to do special pedagogics with those who weren't motivated, was not my force. With time I got more and more involved in work other than the teaching, in the union and in work with terminology and teaching aids, and felt that I had more to contribute with in these fields.

But it wasn't appreciated by all that someone wished to go beyond what was common and decided. When I applied for 50 percent unpaid leave of absence to do my main subject in vocational pedagogics, the principal and the school board turned the application down, the motive being that it wouldn't be useful to the school. The attitude to development of the school had turned completely since the test period barely a decade earlier. Initiatives to develop the school and further pedagogical education had become a threat to the inner peace at school. It was this rejection that made me go the whole way. I quit my job without knowing how I would cope, but this far I have managed without bothering the employment office.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

Other articles in Sami School History 2